- Tags:

- Japan / JAPAN Forward / Swords / WWII

Related Article

-

Never Lose Your Page Again With This Easy-To-Make Bookmark!

-

Canadian Olympics reporter falls in love with 7-Eleven in Tokyo, charms Twitter with convenience store odyssey

-

Burger King Japan’s Ugly Cheese Beef Burger says goodbye to pretty eating

-

This Ping Pong Prodigy’s “Bowling” Trick Shots Are Amazing

-

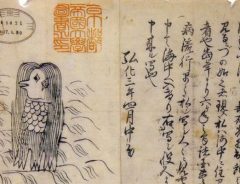

Japanese artists summon anti-plague demon to battle coronavirus

-

Unicorn Taiyaki Fish Ice Creams Give Japanese Traditional Snack Colorful New Look

(By Paul Martin)

In recent times, there have been many cases of war loot being repatriated to the original owners, their descendants, or country of origin. French President Emmanuel Macron wants to return looted treasures to France’s former African colonies, and the British Museum recently returned eight objects that were looted from the National Museum of Iraq in the turmoil following the Iraqi War. There is another huge movement to return Nazi war loot that mostly targeted art treasures during the second world war.

Many of today’s museums are carefully screening their collections to ensure that these do not have any of those pieces in their collections and, if they discover one, to take the appropriate steps to return them.

The root of this conundrum is a difficult concept for people to overcome. Victors feel entitled to take items as prizes from their enemies, referring to them as the spoils of war.

War-end Confiscation of Japanese Swords

Which brings us to Japanese swords.

Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, Japanese soldiers were required to surrender all arms, including their swords. Looking at the many photographs, it appears that special ceremonies were held specifically for the surrender of swords not only inside Japan, but in many of the conflict areas, Papua New Guinea, Borneo, Wake Island, etc.

Many of the soldiers who had taken their family blades to war were under the impression that their swords would be returned to them at a later date, so a large number of swords were handed over with a name tag (commonly known as surrender tags) attached, with personal details of the owner written on it. However, these swords were never returned.

Instead, many were distributed among, or taken by, soldiers of the allied forces and taken back to their home countries.

Disappearance and Destruction of Priceless Family History

Inside Japan an edict was issued by the allied forces for the confiscation of all weapons — including swords — from even the general public for their destruction. The edict was stopped after the historical, cultural, and artistic importance of Japanese swords was pointed out to GCHQ, but not until many swords had been shoveled into furnaces, scuttled on barges in Tokyo Bay, or buried (like 40 swords recently discovered at a Nishi-Tokyo School).

Around 5,000 swords were confiscated and kept at a United States military facility in Akabane, Tokyo. They are now known as Akabane-to (Akabane swords).

Many of these swords confiscated inside Japan made their way into the hands of allied personnel and out of country. The most famous of these swords that were never to return was the Honjo Masamune. The sword was an heirloom of the Tokugawa family. Even today, its whereabouts, or fate, remain unknown.

Like the Honjo Masamune, many of these swords, as opposed to their mass-produced counterparts for the war effort, are considered art objects and had been passed down in families for generations.

Written by Japan ForwardThe continuation of this article can be read on the "Japan Forward" site.

Do Japanese Art Swords Surrendered after WWII Constitute War Loot?