- Tags:

- Japanese language / katakana / loan words / wasei eigo

Related Article

-

Ask your Japanese friends this ONE question!

-

“Funny Cool” Japanese text tee makes impact at Milan runway show, amuses Japanese Twitter

-

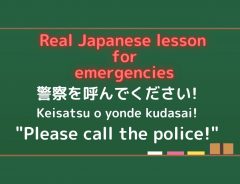

Japanese teacher’s real phrases to use in Japan: Emergencies [audio included]

-

There’s something fishy about this Rengoku bread spread and French people might not like it

-

Japan’s “hardest food”? You may be in for a surprise when you learn this Japanese word

-

How to study for the JLPT? Asking an N1 holder with full marks! [interview]

Japanese is certainly a very complicated language. What with Chinese characters whose readings change depending on the word, and two sets of phonetic characters, it’s hard enough to get started learning Japanese, never mind mastering the language.

When I was studying at a Japanese language school, I always envied my Chinese and Taiwanese classmates who, having grown up with kanji, sped through reading assignments. It didn’t matter that they couldn’t read the text aloud, at least they could make sense of the text.

But there was always one glimmer of hope for westerners studying Japanese: Katakana words. Katakana is a Japanese syllabary that is used for foreign loan words and country names, as well as onomatopoeia, plant and animal species, company names, etc.

Japan’s lenient use of foreign words became a joke whenever Sensei asked one of us what something in katakana meant in English.

Sensei permission from Gurachi Phoenix

Sensei: “Tomi-san, mai pēsu wa, eigo de nan desu ka?”

(Tomi, what does “mai pēsu” mean in English?)

Tomi: “Eigo de issho desu yo. ‘Mai pēsu’ wa eigo de ‘my pace’ to iimasu yo.”

(it’s the same in English. My pace.)

Sensei: “Aaa, sō desu ka? Omoshiroi desu yo ne.”

(Ooh, really? Well, that’s interesting, isn’t it?)

Speak English Like You’re Japanese

Japanese aren’t known for having great English skills. Despite English education in Japan starting at the age of 10, there are many reasons why the system is flawed. One cause is the dependency on katakana characters to explain pronunciation.

Photo by Mujo

Photo by Mujo

Many Japanese learn English vocabulary by rote memorization using thick books. The words are accompanied by IPA (International Phonetical Alphabet), but also include katakana spellings. I’m sure you can guess which one most students rely on.

Katakana’s detrimental effect on English education can’t be stressed enough. But Japan’s education system isn’t the point of this article. So what am I getting at?

Stick with me. Going back again to my language school days, there was this one Indian student named Gurachi. He had a way of striking up a conversation and becoming friends with anyone. But his vocabulary was awful and he was always too busy with his work to focus on his studies.

The secret to his conversational success? Speaking English in a very Japanese manner. Anytime he got stuck on an English word he didn’t know in Japanese, he’d just pronounce it more like a katakana word. Voilà!

Although many Japanese tourists may struggle abroad due to their unique pronunciation, you can certainly use katakana to your advantage and feel like you’re speaking Japanese, even if it’s really just English. But there are some special cases when your English may be interpreted as something very different...

Wasei Eigo

“Wasei Eigo” 和製英語 literally means English made in Japan. These words not used by native English speakers, but rather are more like pseudo-English words used by Japanese in daily life. Wasei eigo is different from foreign loan words adopted in Japanese from European languages.

As illustrated in the cartoon above, “my pace” is a phrase commonly used by Japanese. Rather than being an actual phrase borrowed from another language, it’s a unique adaptation of English words.

Here are some more examples of common foreign loan words and Wasei eigo:

© Pakutaso

Further Reading on Wasei Eigo

Of course, this is just a shortlist of some of the more commonly used pseudo-English. For a more comprehensive list here are a couple great resources for your reference below.

Wikipedia’s List

Tofugu, the creator of WaniKani, a great kanji learning application, also has a useful list of phrases and example sentences to give some more context.