- Tags:

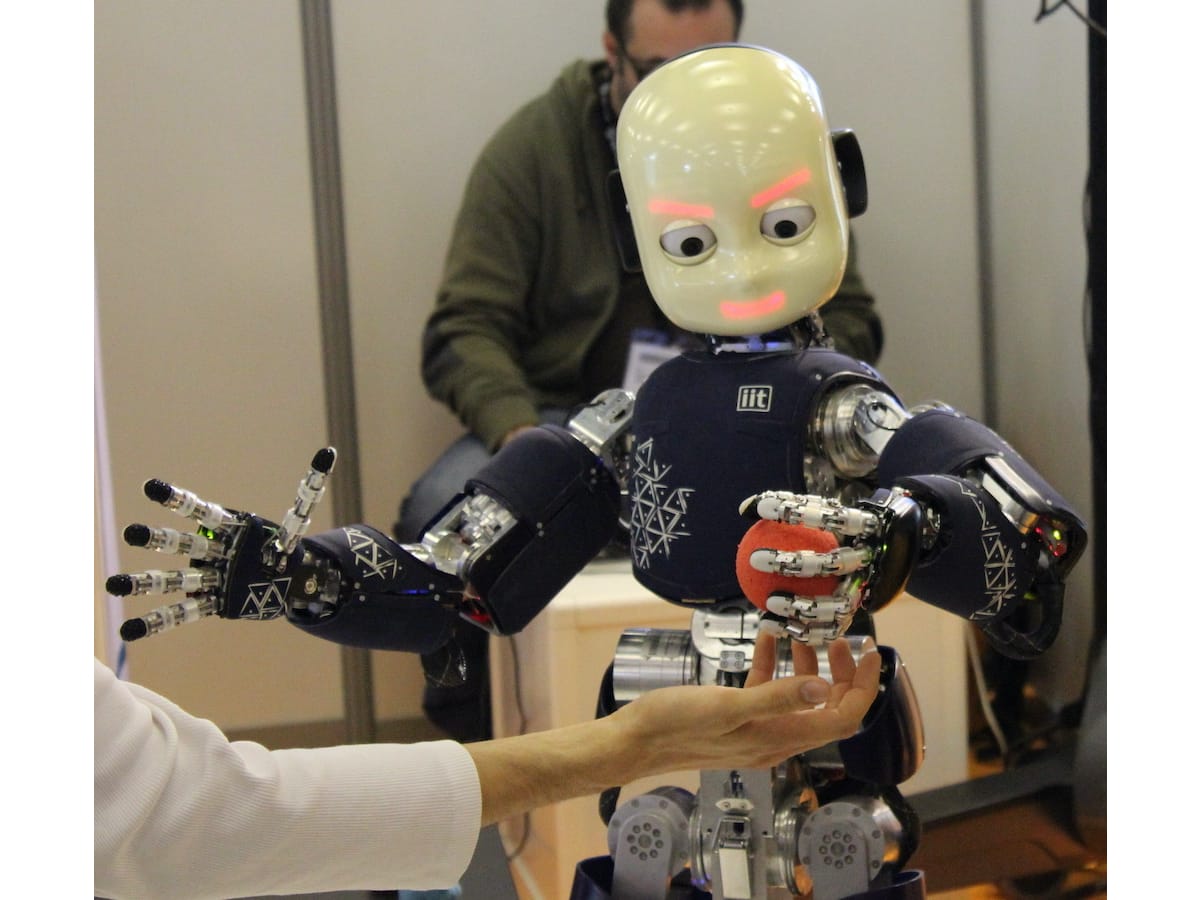

- automaton / karakuri ningyō / Robot

Related Article

-

Android Geminoid-F Stars In Japanese Film ‘Sayonara’

-

Tokyo Metro tests its first unmanned security and cleaning robot at Tsukishima Station

-

My strangely enjoyable experience staying in Japan’s Henn Na Hotel

-

Japan Launches World’s First Idol Robot Mannequin Business Solution [Video]

-

Star Wars R2-D2 Delivers Its Frigid Beer To Your Home Next Month

-

We Tried The World’s First Consumer Model Entertainment Exoskeleton Suit by Skeletonics

Robots and Japan are practically synonymous. The Japanese government and some of its biggest corporations see the 21st century as one of ‘human co-existence with robots’ and are spending billions on research into robotics.

Robots have a long history in Japan. They have always been seen rather differently than they are in the West, where people tend to have a ‘Frankenstein complex’, always worried that sooner or later robots will gang up and try to wipe out humanity.

The Japanese, on the other hand, have only love and affection for their robots. They see them as friends, perhaps because Shinto teaches that not only humans and animals, but also animals, plants and even inanimate objects like rocks and rivers have spirits. This animistic impulse extends to machines and robots too.

Robot "Beogradska šaka". Slikao Goldfinger (CC by SA 3.0)

A thinktank like the Mukta Institute, which promotes a religious understanding of robots, could surely only exist in Japan. The Institute provides consultation to corporations such as Honda and Omron on automation and robotics. They do this by promoting a fusion of high technology, creative thinking and Shintoism. Members regularly meet to recite Buddhist scriptures, meditate and consider solutions to technological problems.

The Japanese love of robots has its roots in puppetry, which has been popular for centuries. Puppets have long performed scenes from traditional myths and legends during matsuri, or festivals. The seventh Tokugawa daimyō Muneharu 徳川宗春 (1696-1764) was a great lover of these karakuri which flourished under his patronage during the Edo period. Muneharu actually banned invention and mechanisation, but he made an exception for dolls and puppets designed for matsuri. As a result, a generation of inventors and scientists turned their skills to developing karakuri ningyō からくり人形, or ‘mechanical dolls’.

Karakuri ningyo in Expo 2005 Museum | KKPCW / CC BY-SA出典:出典名

The art and science of making karakuri ningyō is described in lavish detail in the three-volume Karakuri: An Illustrated Anthology, which was published in 1796. The anthology explains the workings of nine types of mechanical doll, with each explanation accompanied by precise diagrams.

The most famous karakuri were produced in the late Edo period, by which time Western clockwork mechanisms had been introduced to Japan. They became the archetypes of what Edo-era intellectuals liked to call wakon yōsai 和魂洋才, or ‘Japanese spirit, western learning’. Such was the respect accorded mechanical puppets that until the late nineteenth century, worn-out puppets were not thrown away or recycled, but buried in special ‘puppet cemeteries.

The most famous Edo era karakuri is the chahakobi ningyō 茶運び人形, or ‘tea-serving doll.’ The host would put a teacup on the clockwork doll’s little tea tray, and it would carry the cup to his guest. When the guest took the tea from the tray, the doll would stop and wait until he’d drunk it. When the guest put the cup back on the tray, it would turn around and walk back to its ‘master’.

Another ingenious robot forerunner is the yumihiki dōji 弓曳童子, or ‘archer doll’, which picks up an arrow and shoots it at a target. It even deliberately misses the target one out of ten times, just to keep the audience in suspense.

Its creator, Hisashige Tanaka 田中久雄 (1799-1881) had a shop in Kyoto called ‘The Hall of Automata.’ He was the first karakuri master craftsmen to start putting his skills to more practical uses. At the end of the Edo era, Japan’s rulers were coming to terms with the need to keep up with western technical innovations and Tanaka was summoned by the daimyo to advise on modernisation.

He soon set to work trying to unravel the secrets of western technology. Within a year, he had built the first working model of a steam locomotive in Japan, quite a feat when you consider that he’d never seen a real locomotive and was entirely dependent on a Dutch reference book for guidance.

Hisashige Tanaka directly contributed to the modern industrialisation of Japan. He was the founder of a company that made some of the country’s first light bulbs, telephones, steam engines and iron bridges, which later became the Toshiba Corporation. Tanaka is known as ‘Karakuri Giemon’ からくり儀右衛門 and has also been called the ‘Thomas Edison of Japan.’

Sakichi Toyoda (1867-1930), the founder of the Toyota chain of companies, was also a karakuri master. Toyoda was from Aichi prefecture, to this day the region most closely associated with the karakuri tradition. It is surely no accident that Aichi is also the most industrialised region of Japan, and the hub of the Japanese robotics business.

If you’d like to find out more about the history of karakuri and their role as forerunners of today’s robots, here are a few tips: