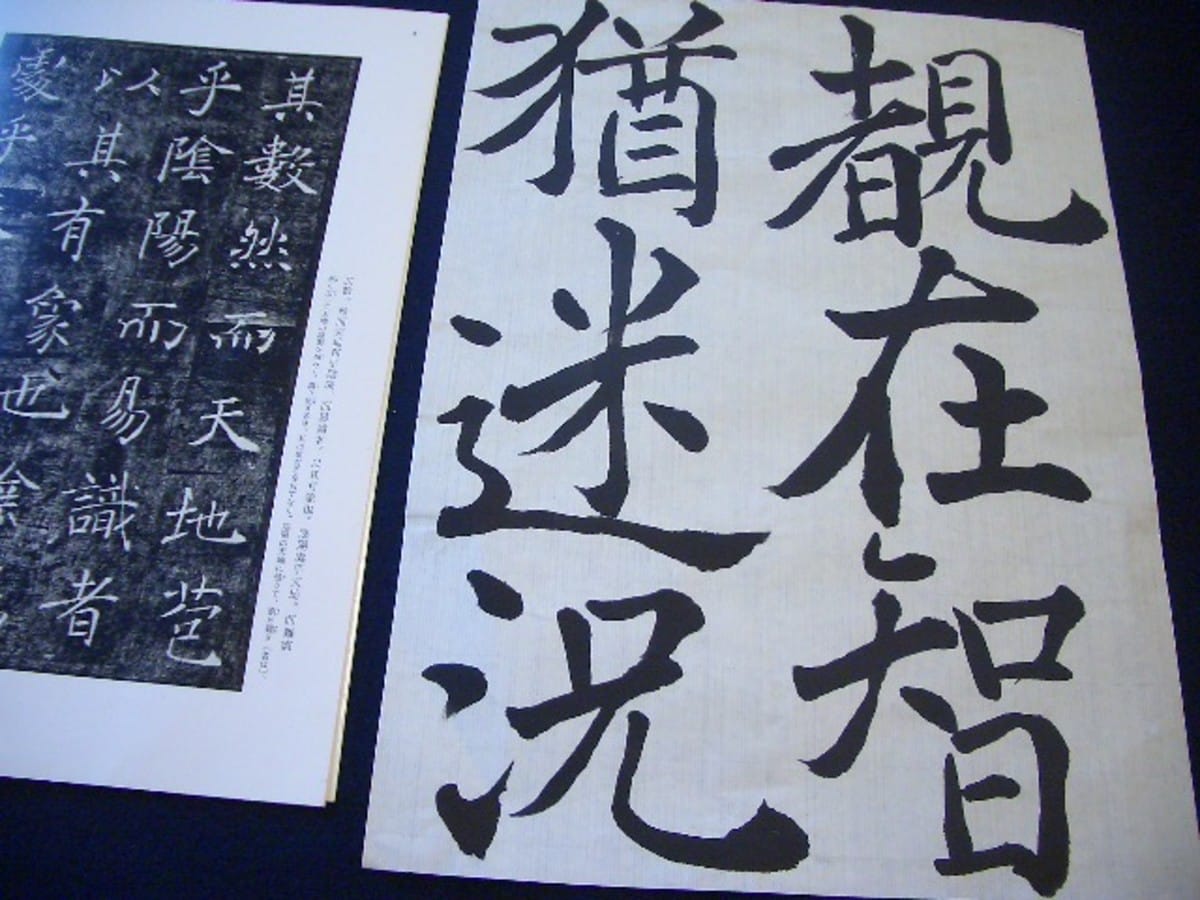

Source: Kanko | © Flickr.com

The Ancient Japanese Art of Death Poems is Incredibly Spiritual and Inspiring

- Tags:

- death / philosophy / poetry / Zen

Related Article

-

Rest in Peace Grape, The Penguin Who Loved a Cardboard Anime Cutout

-

This Miniature Zen Garden Is All You Need To Create Your Own Spiritual Oasis

-

Smart Bonsai Follows You Around, Quotes Goethe, in TDK’s Vision of The Future

-

Koa The Cat Sinks Deeply While Sleeping

-

The Best Temples in Kyoto to Experience Zen Meditation

-

Artist creates breakfast moment of Zen with awesome Japanese rock garden toast

In Japan, there is a traditional poem known as 辞世, jisei, or death poem. With origins in Zen Buddhism, such poems are written by authors, often samurai or monks, as they approach their final days. These poems highlight themes of impermanence and transience, concepts central to Zen Buddhism. Like other aspects of Japanese culture, Buddhist spirituality emphasizes the importance of death as an integral part of life. As such, exceptional pieces are transcendent and suggestive of 悟り, satori, or enlightenment.

While not necessarily structurally related to 俳句, haiku, death poems borrow similar conventions. Most are written as short poems, known as 短歌, tanka. While some may be haiku, the tanka structure is typically longer and more varied in composition.

The most famous collection of Zen death poems I am aware of is “Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death,” compiled by Yoel Hoffmann. Nevertheless, I thought it would be enlightening to scour the web in search of inspiring entries and share them.

Zen Death Poems

In a post by The Japan Times, editors replicated the death poem of Zen master Kozan Ichikyo. Before his death, he wrote the poem:

Empty-handed I entered the world

Barefoot I leave it.

My coming, my going—

Two simple happenings

That got entangled.

The sort of base simplicity of the piece is striking. It points to the randomness of life and existence that undermines the importance we give it.

On a blog, Aalif posted several death poems that were striking. Here are a few:

Breathing in, breathing out,

Moving forward, moving back,

Living, dying, coming, going—

Like two arrows meeting in flight,

In the midst of nothingness

Is the road that goes directly

to my true home.

That was attributed to Gesshu Soko. Like Ichikyo’s poem, it points to the sort of trivial intersection that comprises our ever-important lived life.

Here is another from Aalif’s blog:

Since time began

the dead alone know peace.

Life is but melting snow.

Attributed to Nandai, the post almost seems envious of the deceased. Perhaps something better awaits on the other side.

More Poems

So, why not keep going? I feel a sense of humbled somberness as I read these.

On her blog, Jan Thomas presented more death poems that she found striking. Why don’t we read a few:

Coming, all is clear, no

doubt about it. Going, all is

clear, without a doubt.

What, then, is all?

Attributed to Hosshin, this jisei resonates a little bit deeper. What is the confidence inherent in our egos? If we trust it, where will it lead us?

And another:

Even a life-long prosperity is but one cup of sake;

A life of forty-nine years is passed in a dream;

I know not what life is, nor death.

Year in year out — all but a dream.

Both Heaven and Hell are left behind;

I stand in the moonlit dawn,

Free from clouds of attachment.

Attributed to Uesugi Kenshin, it's hard to say much about this poem. It underlines that our experience is fleeting. Nevertheless, I connect with the line, "Even a life-long prosperity is but one cup of sake." I guess, no matter how good you have it...

A Few More

Finally, Chris Kincaid of Japan Powered wrote a piece on jisei and reposted a few poems that are worth a read:

There is no death;

there is no life.

Indeed, the skies are cloudless

And the river waters clear.

Attributed to Taiheiki Toshimoto. I like this one because, even though it is centered upon death, it hints at a reality that is not burdened by the negativities that humans often attribute to their everyday experiences.

How about one more:

On a journey, ill;

my dream goes wandering

over withered fields.

Attributed to the legendary Basho. If you don’t know Basho, he is likely the most revered Japanese poet. As such, I think this poem needs no explanation. Hopefully, readers can find a new appreciation for life in the depth of these death poems.