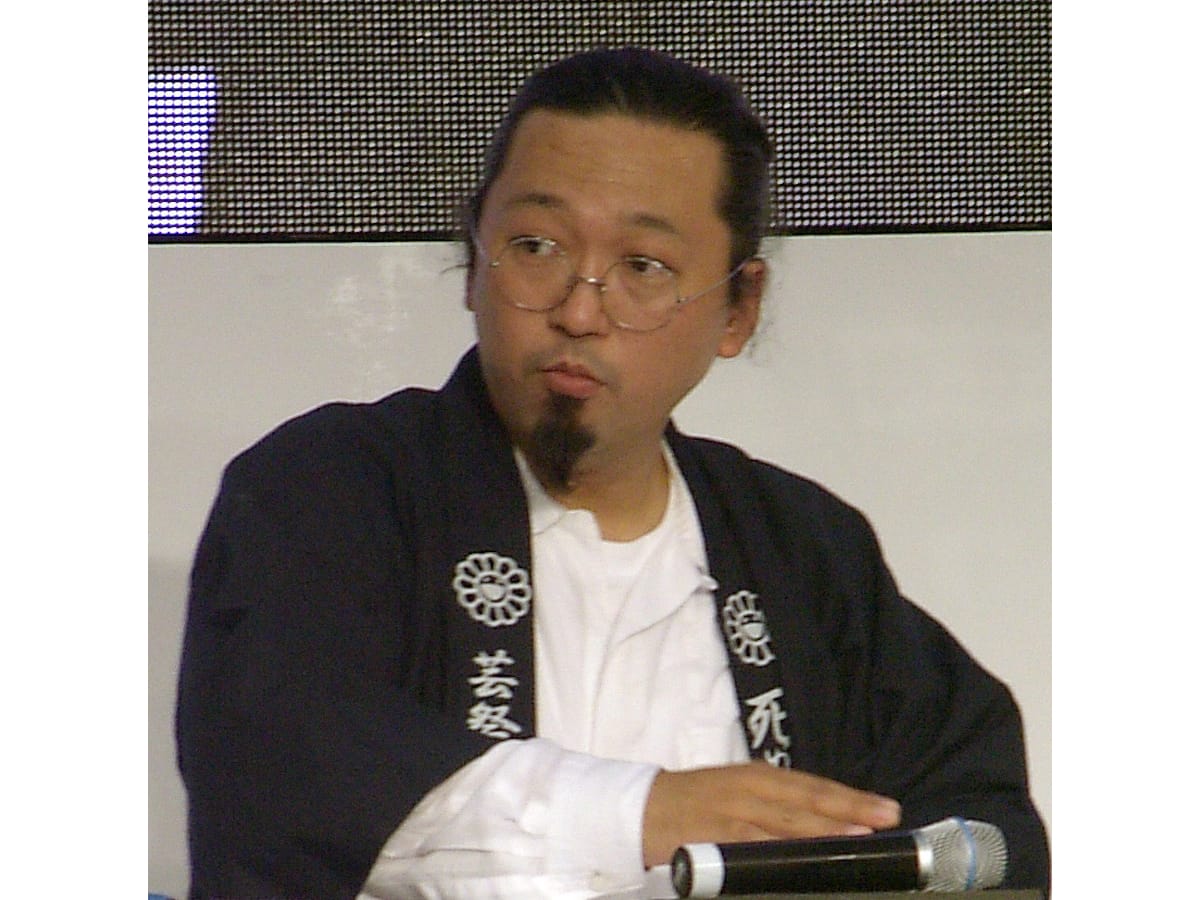

Source: Yamashita Yohei from Tokyo, JAPAN (CC by SA 2.0)

Takashi Murakami: Japan’s coolest artist on kawaii culture

- Tags:

- Otaku / superflat / Takashi Murakami

Related Article

-

Never Eat Alone With This Virtual YouTuber’s Anime Girl Dining Experience

-

Japanese otaku share their stylish transformation photos on Twitter

-

Ikebukuro Bar Offers Cosplayers Free All-You-Can-Drink Libations for a Month

-

Employment Agency’s Hi-Tech “Photo Booth” Prints Resume Of Your Future Self

-

Japanese Idol Group Puts On Hazmat Suits To Hug Fans At Event

-

“Otaku House” Promises Cheap Lodging and Fun Experiences For Otaku Tourists

Takashi Murakami is one of Japan’s best-known modern artists. In 2008, he was named one of Time magazine's ‘100 Most Influential People’, the only visual artist to make it on to the list. Murakami works in a variety of media: painting, sculpture and performance art, but also fashion, music video and animation.

He coined the term ‘superflat’ to describe his approach to art making, which, he says, builds on the legacy of flat, two-dimensional imagery from Japanese art history. With its emphasis on surface and use of dramatic flat blocks of colour, it’s quite distinct from the western approach to art and goes a long way in explaining the importance of manga and anime in Japan.

But ‘superflat’ is more than an artistic style. Murakami also uses it to describe post-war Japanese society. By his reckoning, differences in social class and popular taste have been ‘flattened,’ such that people no longer make much distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.

‘Superflat’ has become a logo, a way for Murakami to sell his art, but also a way of ruffling feathers in western art markets. “Japanese people accept that art and commerce will be blended,” he says. “In fact, they are surprised by the rigid and pretentious Western hierarchy of ‘high art.’ In the West, it certainly is dangerous to blend the two because people will throw all sorts of stones. But that's okay—I'm ready with my hard hat.”

Soho Contemporary Art (CC by SA 3.0)

Murakami is interested in how and why Japan’s ‘superflat’ culture ended up being so childish. He says he wants to explore “the replacement of a traditional, hierarchical Japanese culture with a disposable consumer culture ostensibly produced for children and adolescents.”

Traditional art and contemporary art certainly seem to be poles apart. In the past, art and culture were rarefied and reserved for the elite. Artisans, merchants, and peasants weren’t expected to be able to appreciate the tea ceremony or noh theatre. Compared to traditional hierarchical culture, today’s ‘superflat’ culture is much more democratic: open to all, easy to understand and completely unintimidating.

But what’s behind what Murakami calls “the infantilization of the Japanese culture and mindset”? Why is Japan’s ‘superflat’ culture so enamoured of pastel colours and baby faces? Why is everything so kawaii? Why is everyone trying to be so relentlessly cheerful? Is it just a reaction to the dour, formalism of traditional art forms like kabuki and calligraphy? Is it just an escape from the adult world, with its ritualised deference and consideration? Or is the young generation just trying to reassure their parents that they don’t mean them any harm?

In 2005, Murakami curated an exhibition in New York City in which he tried to come up with some answers to these questions. He called it ‘Little Boy’, making an explicit connection between infantilism and the atomic bomb that the Americans dropped over Hiroshima in 1945.

By his reckoning, the bomb ensured that post-war, Japan’s relationship with the United States would be marked above all by subservience. Japan was not allowed to rebuild its army and became dependent on the Americans for its defence. Japanese foreign policy followed the Americans’ lead, and Japanese people became slavish imitators of American social norms.

Japan was effectively castrated, kept in a state of perpetual childishness. This disjuncture - between the dark, brooding, moralising male past and the airy, light, feminine present – is at the heart of ‘superflat’ culture. Think of it as a belated celebration of womanhood. Japanese women have spent centuries trying and failing to find a place in patriarchal society. Now Japanese men are trying and failing to adjust to post-material life. You can see this in otaku culture, with its sexual confusion, immersion in play, and anti-sociability. Takashi Murakami has channelled otaku culture into the art world.