Source: Okinawa Soba (Rob) / © Flickr.com (CC by SA 2.0)

A Japanese history lesson: who were the burakumin?

- Tags:

- burakumin / Discrimination / outcaste / untouchable

Related Article

-

Japanese women face discrimination, victim blaming, harassment as they seek equal rights

-

Come Study in France! Says Embassy to Female Medical Students After Japan’s Discrimination Scandal

-

“I saw two men holding hands…”: Japanese store has perfect response to prejudiced complaint

-

Japanese Train Conductor Apologizes To Passengers For “Having So Many Foreigners On Board”

-

Shedding Light On Japan’s “Shady School Rules”: Japanese Twitter Users Speak Out

-

Frustration Grows With Japanese Companies Prohibiting Women From Wearing Glasses

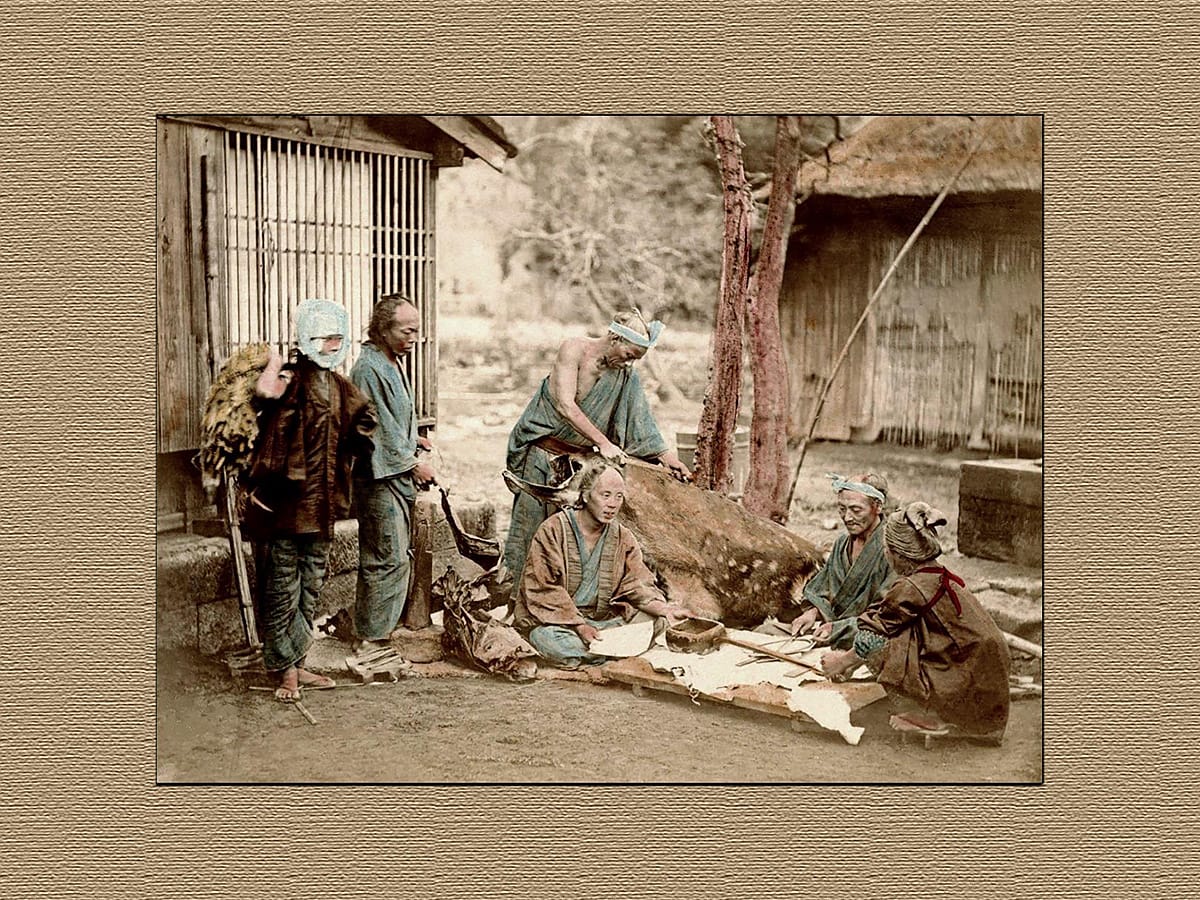

Header image: A man scrapes the hide of a slaughtered deer, while another holds a piece of finished cat skin to cover an old shamisen. This photograph, taken in 1873, purports to be the only known photograph of burakumin from the Meiji era. In fact, it was staged by the photographer, using friends pretending to be burakumin.

Sooner or later, the long-term foreign resident of Japan keen to get under the skin of the country will come across the burakumin. The idea that a country as advanced as Japan might have an ‘untouchable’ cast, akin to the Dalits of India, always comes as a shock. Since discussion of the subject is still considered taboo by many Japanese, here is a handy primer.

The term ‘burakumin’ is something of a misnomer. It literally means ‘village people,’ in reference to the separate villages that the ‘untouchables’ were once forced to live in. In feudal times, they were pejoratively known as eta (穢多, literally, “an abundance of filth”) because of their association with ‘deathly’ industries like tanning and butchering, which Buddhists believed polluted the souls of those who engaged in them.

Not that all burakumin worked with dead animals. In feudal Japan, there were plenty of other outcastes, including ex-convicts and vagrants. They typically worked as town guards, street cleaners or entertainers, and were collectively referred to as hinin (非人, “non-human”).

Jiichiro Matsumoto, chairman of the Kyūshū Levelers Association, known as ‘the father of buraku liberation’ | BLL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Burakumin were the scapegoats and whipping boys of feudal Japan. Their position on the bottom rung of a fiercely policed hierarchy enhanced the social status and self-respect of everyone else, from the peasant to priest to samurai. Such was the strength of popular prejudice against burakumin that not only were they forced to live in separate communities, their villages were not even marked on maps. They were effectively invisible.

Why were the poorest and most marginalised members of feudal Japanese society held in such low regard? All that can be said by way of mitigation is that life in the Edo era was incredibly harsh, particularly in the countryside, where most burakumin lived. Peasants handed over 40-50% of their crop to the local daimyo (feudal lord). This rose to 70% when times were hard, and they often were: there were 15 major famines during the Edo era.

Feudal era life was not just poor, it was oppressive. The daimyo, and the samurai who served him, regulated the peasants’ lives to the minutest degree. Peasants were expected to be frugal and diligent, but also submissive to their social superiors. How they dressed, where they went, and even their haircuts were prescribed.

Tadashi Yanai, founder and president of Uniqlo, is one of many public figures to have burakumin heritage | Jigneshhn, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The belief that burakumin were spiritually ‘polluted’ by contact with the dead ebbed and flowed throughout the Edo era. Ironically, the treatment of the burakumin was cruellest in the 19th century, when the ‘double-bolted country’ began to come under pressure from the outside world. New restrictions were imposed on burakumin in 1819, perhaps to appease peasants made anxious by the gradual enfeeblement of Edo society.

When the Edo era came to an end in 1868, the population of Japan stood at 30 million, of whom 1.8 m were samurai, 3-4 m were townspeople, and 500,000 were burakumin.

The newly formed Meiji government set about dismantling the old feudal hierarchy. People were reclassified as either kazoku 華族 (peers), shizoku 士族 (gentry) or heimin 平民 (commoners). Commoners were given deeds to the land they worked and common land became the property of the state. Commoners were required to adopt family names (until then, they’d only had first names) and were free to travel, wear what they liked and have their hair cut however they liked.

Among the myriad decrees issued by the new government was one that gave legal equality to burakumin and another that lifted the ban on meat consumption. Although the practice of eating meat had existed even during the Edo period, many Japanese opposed the lifting of the ban. Abattoirs and those who worked in them were met with open hostility from local residents in villages across Japan.

In 1875, 26,000 peasants in Okayama prefecture rioted, demanding that the shinheimin 新平民 - ‘new commoners’ – be relegated to their former status as burakumin. Later that year, 100,000 peasants rioted in Fukuoka, demanding the same.

Toru Hashimoto, the former mayor of Osaka, also has burakumin heritage. | Ogiyoshisan, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As Japan began to industrialise, the burakumin became part of the new workforce. At the heart of industrialisation was coal production, which went from a million tons a year in 1883 to 31 m tons a year in 1919. The biggest mines were at Miike and Aso, both in Kyushu. The government sent burakumin, prisoners, debtors, and Koreans into the mines. Living conditions were awful. Crew bosses were usually underworld thugs, often fellow burakumin, who were thought necessary to keep ne’er-do-well miners in check.

In the years following the end of World War One, burakumin began to organise for an end to discrimination and true equality. The movement for equal rights divided into two camps. On one side was the ‘assimilation’ (同和, dōwa) movement, which wanted to see improvements in living standards in burakumin communities and integration with mainstream Japanese society. On the other was the more radical ‘levellers’ (水平社, suiheisha) movement, which sought to confront and challenge those who discriminated against burakumin. The Suiheisha – Levellers’ Association – was founded in 1922.

Socialism and communism were rising forces in the interwar years, and many burakumin threw in their lot with their fellow workers. Kitaharu Taisaku became notorious after trying to present the emperor with a petition protesting against discrimination against the burakumin. But as the conflict between organised labour and the bosses grew sharper, other burakumin crossed the tracks. Some found work as strike breakers, others worked in prostitution and gambling for the yakuza. When the militarists came to power in 1936, some burakumin entrepreneurs got rich supplying leather boots to the army.

Thanks to urban development and policies designed to raise living standards, burakumin villages had ceased to exist in many parts of the country by the 1960s. But in Kansai, many burakumin still lived in slums and suffered the attendant blights of illiteracy, lower educational achievement, and lower economic status.

A government survey conducted in 1965 found that 70% of people thought that burakumin were of a different race than other Japanese people. With discrimination so widespread, it’s hardly surprising that burakumin were insular. In 1967, a survey found that 90% of them still married other burakumin.

Starting in the 1980s, the government made concerted efforts to address the material deprivation and marginalisation suffered by burakumin communities. Still, discrimination persists up to the present. In Kansai, people often associate burakumin with squalor, unemployment and criminality. This may be because burakumin account for about 70% of the members of the Kobe-based Yamaguchi-gumi, the biggest yakuza syndicate in Japan.

Today, there are some two million burakumin, living in approximately 5000 settlements. Most are located in western Japan, particularly around Kyoto and the Inland Sea, and three-quarters of them are in rural areas.

Outside the Kansai region, many people are often not even aware of burakumin, and those that are usually think of them as part of feudal history. Due to the taboo nature of the topic, burakumin issues are rarely covered by the media, and people from Kanto are often shocked to discover that there is a Buraku Liberation League.

Prejudice against burakumin is certainly less rife in eastern Japan. According to a survey conducted by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 2003, 76% of Tokyo residents would not change their view of a close neighbour if they discovered that they were burakumin.

Encouraged by activist groups like the Buraku Liberation League, young people of burakumin heritage have become more vocal in organizing and protesting against discrimination since the 1980s. Burakumin still encounter prejudice in some quarters when looking for work, and old-fashioned parents might object if they find out that their son or daughter’s partner is from a burakumin community. Nonetheless, the fact that, these days, between 60 and 80% of burakumin marry non-burakumin, is evidence that the movement for equality and integration has been largely successful.

Sources