- Tags:

- city layout / Tokyo / topography

Related Article

-

Creme Brulee Crepes are the Most Genius Dessert in Harajuku

-

New Katana Cafe In Tokyo Lets You Look At Awesome Swords While You Dine

-

Japanese sweets store’s 12,960 yen White Truffle Butter Sandwich is definitely a luxury treat

-

Sushi Restaurant Serves Tiny Plates Of Miniature Sushi — For Free!

-

Isetan’s Sui no Za Is A Must Stop By Emporium Of Sake And Beer From All Over Japan[PR]

-

We Tried Wine Frappuccinos And Tarts At Tokyo’s New ‘Starbucks Evenings’!

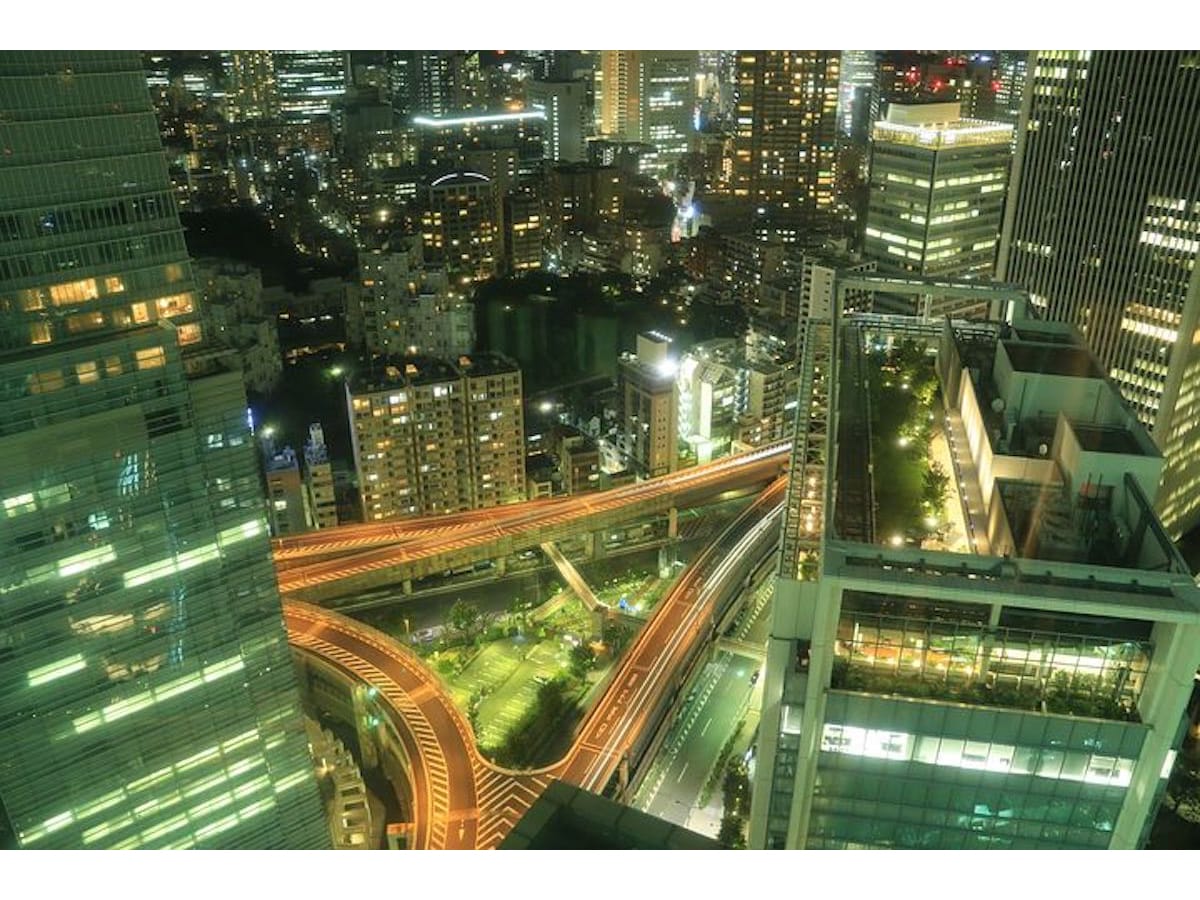

You might not think so looking out over Tokyo from one of its giant skyscrapers, but the modern city owes its chaotic appearance to the layout of old Edo, which was in turn based on height differences in the natural landscape.

Tokyo sprawls across the Musashino Plain and the lower coastal plain on the west side of Tokyo Bay. The eastern part of the plain is called Yamanote (the highlands) and is 10-20 metres higher than the strip of land that runs along the coast.

West of Shinjuku, the plain is pretty flat, but as you head east towards Tokyo Bay, meandering rivers - the Shakujii, Shibuya and Meguro River - start cutting channels into the plain. Aside from the rivers, there are also lots of brooks and streams that bubble up from springs on the plain. These springs create basins, which are usually surrounded by hills on three sides.

1500年前の古墳, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The higgledy-piggledy topography of the eastern edge of the Musashino Plain explains why there are so many hills and gullies in central Tokyo. It comes to an end at a ridge, which runs from Yanaka in the north to Shinagawa in the south. East of the ridge, the land is flat as far as the bay.

In the Edo period, the feudal lords and samurai built their homes on the higher ground and had gardens laid out on the slopes around their properties. The peasants lived in the low-lying basins and on the coastal plain, amid the fields and rice paddies where they worked. As the settlement around Edo castle grew, these low-lying areas became residential neighbourhoods for commoners and townspeople. The low ground east of the castle became known as shitamachi 下町 – downtown.

Because the basins to the west of the castle were often surrounded on three sides by cliffs, it was hard to move between the high ground and the low ground. This suited the feudal lords and samurai well, for it allowed them to keep the lower ranks out of sight and out of mind. They built few streets connecting their neighbourhoods with the low ground, which is why you see so many flights of stone steps in the centre of the city.

In the Edo period, cemeteries tended to be on the valley floor, which only reinforced the impression that these stone stairs connected the divine world of the uplands to the worldlier realm of shitamachi.

This cemetery in Roppongi was built on low ground surrounded by hills, where the samurai had their homes. | Peter Kaminski / © Flickr.com CC by SA 2.0

To ensure a tight grip on the commoner population, the samurai built high wooden gates to separate one neighbourhood from another. These gates were locked at night. Shitamachi neighbourhoods were at risk of flooding, and because the houses were made of wood and closely packed together, they were also prone to fire.

You might think that strict control, close proximity and ever-present danger would lead people to turn on one another. But in Edo, they had the opposite effect, binding the residents of each neighbourhood into remarkably coherent and effective social organisations.

When the feudal era came to an end in 1868, the new Meiji government confiscated the feudal lords’ estates and repurposed them as government institutions, parks, hotels and embassies. Over the course of the next hundred years, other large institutions and corporations, which also needed big plots, bought up the land that used to belong to the samurai on the higher ground.

The neighbourhoods of central Tokyo are characterised by staircases that connect poorer low-lying neighbourhoods with wealthier ‘highland’ neighbourhoods. | Hisagi, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The division between highland and lowland, uptown and downtown, rich and poor can still be seen in the layout of modern-day Tokyo. Look down into one of the basins of central Tokyo, and you’ll see that the plots tend to be smaller than those you find on the higher ground.

That’s because, having been subdivided countless times, property developers found it hard to consolidate these little plots into larger plots. So they built few large buildings on the lower ground and instead turned their attention to the higher ground.

As a result, neighbourhoods on higher ground tend to be more spacious, more commercial and wealthier, while most of central Tokyo’s machiya 町屋 – the small townhouses that make up most residential neighbourhoods – are either in basins or further east in shitamachi.

The layout of old Edo has also determined the layout of the city’s biggest streets, which tend to follow the ridges between valleys. These roads are often lined with tall buildings, which form a kind of shell around the low-lying, cosier neighbourhood inside.

This is called the ‘egg and shell’ pattern. Low-rise residential areas – the eggs – are surrounded by a shell of high-rise office buildings that face the larger streets that run around the border of the neighbourhood. Thanks to these protective ‘shells’, Tokyo remains, despite its gargantuan size, a city of pedestrians, bicycles and surprisingly quiet residential neighbourhoods.

It’s not always easy to see traces of old Edo in modern Tokyo. After the disaster of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, and the firebombing of Tokyo at the end of World War Two, wholesale changes were made. The many small waterways that used to run through the low city were filled in with the rubble of the ruined city and many of the basins and gullies in the centre of the city were levelled to make way for bigger neighbourhoods. Yet, in spite of these dramatic changes to the layout of central Tokyo, the essential character of its neighbourhoods remains remarkably unchanged from the Edo period.